As you heard, I’m a physicist. And I think the way we talk about physics needs a little modification. I am from just down the road here; I don’t live here anymore. But coming from round here means that I have a northern nana, my mum’s mom. And Nana is very bright; she hasn’t had much formal education, but she’s sharp. And when I was a second-year undergraduate studying physics at Cambridge, I remember spending an afternoon at Nana’s house in Urmston studying quantum mechanics. And I had these folders open in front of me with this, you know, hieroglyphics – let’s be honest. And Nana came along, and she looked at this folder, and she said, “What’s that?” I said, “It’s quantum mechanics, Nana.”And I tried to explain something about what was on the page. It was to do with the nucleus and Einstein A and B coefficients. And Nana looked very impressed. And then she said, “Oh. What can you do when you know that?“

“Don’t know, ma’am.”

I think I said something about computers, because it was all I could think of at the time.

But you can broaden that question out, because it’s a very good question – “What can you do when you know that?” when “that” is physics? And I’ve come to realize that when we talk about physics in society and our sort of image of it,

we don’t include the things that we can do when we know that. Our perception of what physics is needs a bit of a shift. Not only does it need a bit of a shift, but sharing this different perspective matters for our society, and I’m not just saying that because I’m a physicist and I’m biased and I think we’re the most important people in the world. Honest.

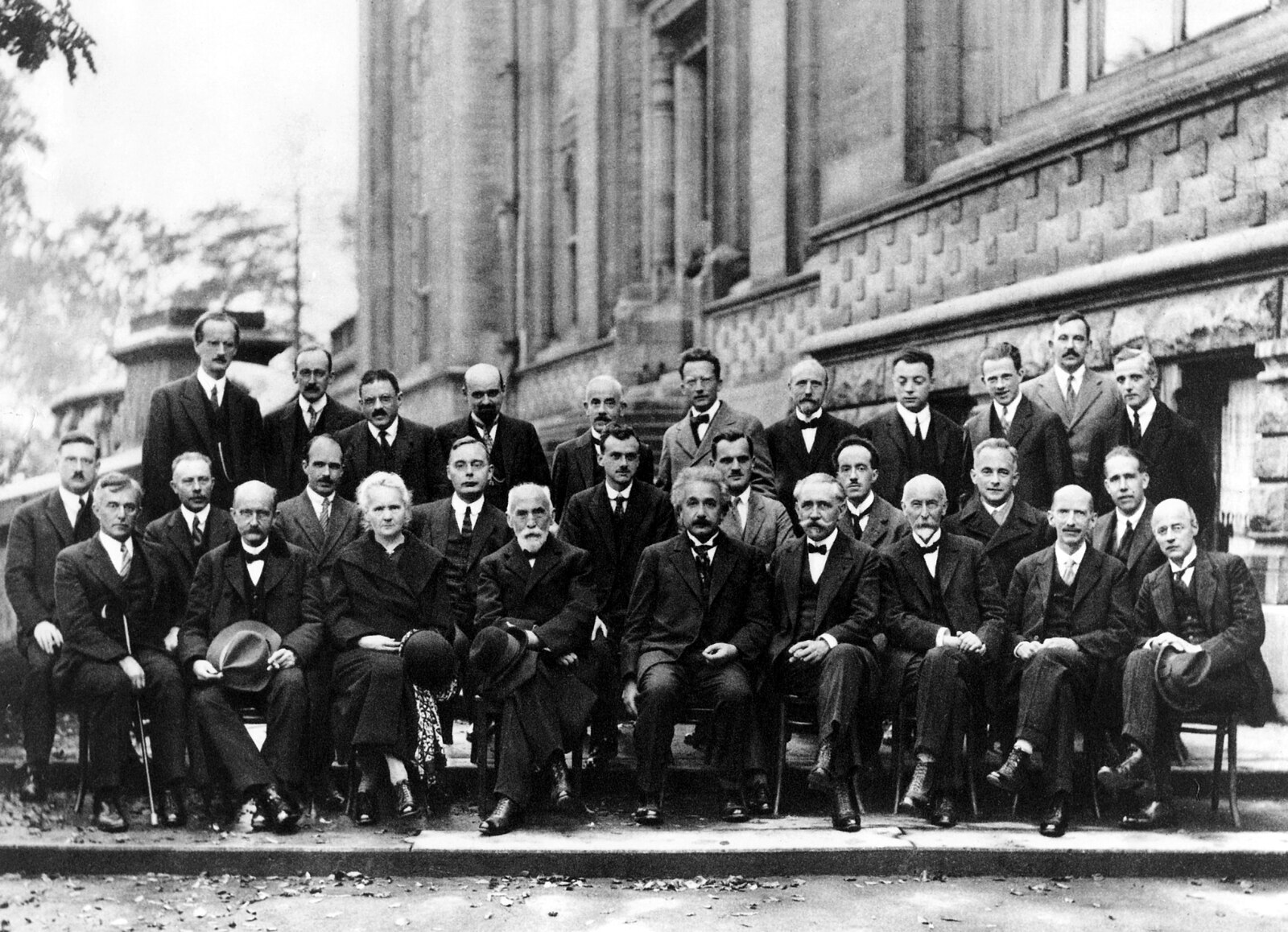

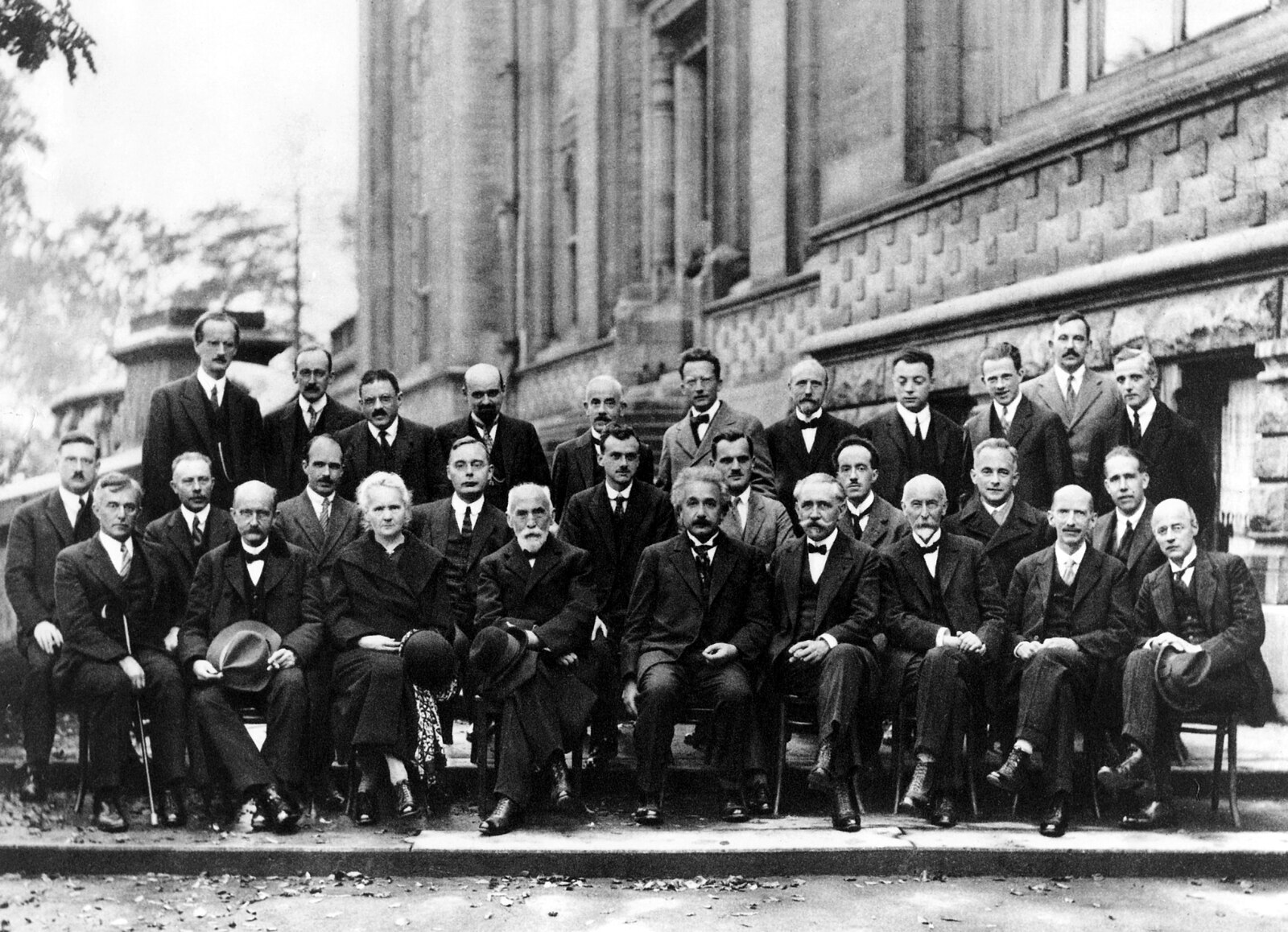

So, the image of physics – we’ve got an image problem, let’s be honest – it hasn’t moved on much from this. This is a very famous photograph that’s from the Solvay Conference in 1927. This is when the great minds of physics were grappling with the nature of determinism and what it means only to have a probability that a particle might be somewhere, and whether any of it was real. And it was all very difficult. And you’ll notice they’re all very stern-looking men in suits. Marie Curie – I keep maybe saying, “Marie Antoinette,” which would be a turn-up for the books – Marie Curie, third from the left on the bottom there, she was allowed in, but had to dress like everybody else.

So, this is what physics is like – there’s all these kinds of hieroglyphics, these are to do with waves and particles. That is an artist’s impression of two black holes colliding, which makes it look worth watching, to be honest. I’m glad I didn’t have to write the risk assessment for whatever was going on there. The point is: this is the image of physics, right? It’s weird and difficult, done by slightly strange people dressed in a slightly strange way. It’s inaccessible, it’s somewhere else and fundamentally, why should I care?

And the problem with that is that I’m a physicist, and I study this. This – this is my job, right? I study the interface between the atmosphere and the ocean. The atmosphere is massive, the ocean is massive, and the thin layer that joins them together is really important, because that’s where things go from one huge reservoir to the other. You can see that the sea surface – that was me who took this video – the average height of those waves by the way, was 10 meters. So this is definitely physics happening here – there’s lots of things – this is definitely physics. And yet it’s not included in our cultural perception of physics, and that bothers me.

So what is included in our cultural perception of physics? Because I’m a physicist, there has to be a graph, right? That’s allowed. We’ve got time along the bottom here, from very fast things there, to things that take a long time over here. Small things at the bottom, big things up there. So, our current cultural image of physics looks like this. There’s quantum mechanics down in that corner, it’s very small, it’s very weird, it happens very quickly, and it’s a long way down in the general … on the scale of anything that matters for everyday life. And then there’s cosmology, which is up there; very large, very far away, also very weird. And if you go to some places like black holes in the beginning of the universe, we know that these are frontiers in physics, right? There’s lots of work being done to discover new physics in these places.

But the thing is, you will notice there’s a very large gap in the middle. And in that gap, there are many things. There are planets and toasts and volcanoes and clouds and clarinets and bubbles and dolphins and all sorts of things that make up our everyday life. And these are also run by physics, you’d be surprised – there is physics in the middle, it’s just that nobody talks about it. And the thing about all of these is that they all run on a relatively small number of physical laws, things like Newton’s laws of motion, thermodynamics, some rotational dynamics. The physics in the middle applies over a huge range, from very, very small things to very, very big things. You have to try very hard to get outside of this. And there is also a frontier in research physics here, it’s just that nobody talks about it. This is the world of the complex. When these laws work together, they bring about the beautiful, messy, complex world we live in.

Fundamentally, this is the bit that really matters to me on an everyday basis. And this is the bit that we don’t talk about. There’s plenty of physics research going on here. But because it doesn’t involve pointing at stars,

people for some reason think it’s not that. Now, the cool thing about this is that there are so many things in this middle bit, all following the same physical laws, that we can see those laws at work almost all the time around us.

I’ve got a little video here. So the game is, one of these eggs is raw and one of them has been boiled. I want you to tell me which one is which. Which one’s raw?

The one on the left – yes! And even though you might not have tried that, you all knew. The reason for that is, you set them spinning, and when you stop the cooked egg, the one that’s completely solid, you stop the entire egg. When you stop the other one, you only stop the shell; the liquid inside is still rotating because nothing’s made it stop. And then it pushes the shell round again, so the egg starts to rotate again. This is brilliant, right? It’s a demonstration of something in physics that we call the law of conservation of angular momentum, which basically says that if you set something spinning about a fixed axis, that it will keep spinning unless you do something to stop it. And that’s really fundamental in how the universe works. And it’s not just eggs that it applies to, although it’s really useful if you’re the sort of person – and apparently, these people do exist – who will boil eggs and then put them back in the fridge. Who does that? Don’t admit to it – it’s OK. We won’t judge you. But it’s also got much broader applicabilities.

This is the Hubble Space Telescope. The Hubble Ultra Deep Field, which is a very tiny part of the sky. Hubble has been floating in free space for 25 years, not touching anything. And yet it can point to a tiny region of sky. For 11 and a half days, it did it in sections, accurately enough to take amazing images like this. So the question is: How does something that is not touching anything know where it is? The answer is that right in the middle of it, it has something

that, to my great disappointment, isn’t a raw egg, but basically does the same job. It’s got gyroscopes which are spinning, and because of the law of conservation of angular momentum, they keep spinning with the same axis indefinitely. Hubble kind of rotates around them, and so it can orient itself. So the same little physical law we can play with in the kitchen and use, also explains what makes possible some of the most advanced technology of our time.

So this is the fun bit of physics, that you learn these patterns and then you can apply them again and again and again. And it’s really rewarding when you spot them in new places. This is the fun of physics.

I have shown that egg video to an audience full of businesspeople once and they were all dressed up very smartly and trying to impress their bosses. And I was running out of time, so I showed the egg video and then said, “Well, you can work it out, and ask me afterwards to check.” Then I left the stage. And I had, literally, middle-aged grown men tugging on my sleeve afterwards, saying, “Is it this? Is it this?” And when I said, “Yes.” They went, “Yes!”

The joy that you get from spotting these patterns doesn’t go away when you’re an adult.

And that’s really important, because physics is all about patterns, and a small number of patterns give you access to almost all of the physics in our everyday world. The thing that’s best about this is it involves playing with toys. Things like the egg shouldn’t be dismissed as the mundane little things that we just give the kids to play with on a Saturday afternoon to keep them quiet. This is the stuff that actually really matters, because this is the laws of the universe and it applies to eggs and toast falling butter-side down and all sorts of other things, just as much as it applies to modern technology and anything else that’s going on in the world. So I think we should play with these patterns.

Basically, there are a small number of concepts that you can become familiar with using things in your kitchen, that are really useful for life in the outside world. If you want to learn about thermodynamics, a duck is a good place to start, for example, why their feet don’t get cold. Once you’ve got a bit of thermodynamics with the duck, you can also explain fridges. Magnets that you can play with in your kitchen get you to wind turbines and modern energy generation. Raisins in fizzy lemonade, which is always a good thing to play with. If you’re at a boring party, fish some raisins out of the bar snacks, put them in some lemonade. It’s got three consequences. First thing is, it’s quite good to watch; try it. Secondly, it sends the boring people away. Thirdly, it brings the interesting people to you. You win on all fronts. And then there’s spin and gas laws and viscosity. There’s these little patterns, and they’re right around us everywhere. And it’s fundamentally democratic, right? Everybody has access to the same physics; you don’t need a big, posh lab.

When I wrote the book, I had the chapter on spin. I had written a bit about toast falling butter-side down. I gave the chapter to a friend of mine who’s not a scientist, for him to read and tell me what he thought, and he took the chapter away. He was working overseas. I got this text message back from him a couple of weeks later, and it said, “I’m at breakfast in a posh hotel in Switzerland, and I really want to push toast off the table, because I don’t believe what you wrote.” And that was the good bit – he doesn’t have to. He can push the toast off the table and try it for himself.

And so there’s two important things to know about science: the fundamental laws we’ve learned through experience and experimentation, work. The day we drop an apple and it goes up, then we’ll have a debate about gravity. Up to that point, we basically know how gravity works, and we can learn the framework. Then there’s the process of experimentation: having confidence in things, trying things out, critical thinking – how we move science forward – and you can learn both of those things by playing with toys in the everyday world.

And it’s really important, because there’s all this talk about technology, we’ve heard talks about quantum computing and all these mysterious, far-off things. But fundamentally, we still live in bodies that are about this size, we still walk about, sit on chairs that are about this size, we still live in the physical world. And being familiar with these concepts means we’re not helpless. And I think it’s really important that we’re not helpless, that society feels it can look at things, because this isn’t about knowing all the answers. It’s about having the framework so you can ask the right questions. And by playing with these fundamental little things in everyday life, we gain the confidence to ask the right questions.

So, there’s a bigger thing. In answer to Nana’s question about what can you do when you know that – because there’s lots of stuff in the everyday world that you can do when you know that, especially if you’ve got eggs in the fridge – there’s a much deeper answer. And so there’s all the fun and the curiosity that you could have playing with toys. By the way – why should kids have all the fun, right? All of us can have fun playing with toys, and we shouldn’t be embarrassed about it. You can blame me, it’s fine.

So when it comes to reasons for studying physics, for example, here is the best reason I can think of: I think that each of us has three life-support systems. We’ve got our own body, we’ve got a planet and we’ve got our civilization. Each of those is an independent life-support system, keeping us alive in its own way. And they all run on the fundamental physical laws that you can learn in the kitchen with eggs and teacups and lemonade, and everything else you can play with. This is the reason, for example, why something like climate change is such a serious problem, because It’s two of these life-support systems, our planet and our civilization, kind of butting up against each other; they’re in conflict, and we need to negotiate that boundary.

And the fundamental physical laws that we can learn that are the way the world around us works, are the tools at the basis of everything; they’re the foundation. There’s lots of things to know about in life, but knowing the foundations is going to get you a long way. And I think this, if you’re not interested in having fun with physics or anything like that – strange, but apparently, these people exist – you surely are interested in keeping yourself alive and in how our life-support systems work. The framework for physics is remarkably constant; it’s the same in lots and lots of things that we measure. It’s not going to change anytime soon. They might discover some new quantum mechanics, but apples right here are still going to fall down.

So, the question is – I get asked sometimes: How do you start? What’s the place to start if you’re interested in the physical world, in not being helpless, and in finding some toys to play with? Here is my suggestion to you: the place to start is that moment – and adults do this – you’re drifting along somewhere, and you spot something and your brain goes, “Oh, that’s weird.” And then your consciousness goes, “You’re an adult. Keep going.” And that’s the point – hold that thought – that bit where your brain went, “Oh, that’s a bit odd,” because there’s something there to play with, and it’s worth you playing with it, so that’s the place to start.

But if you don’t have any of those little moments on your way home from this event, here are some things to start with. Put raisins in fizzy lemonade; highly entertaining. Watch a coffee spill dry. I know that sounds a little bit like watching paint dry, but it does do quite weird things; it’s worth watching. I’m an acquired taste at dinner parties if there are teacups around. There are so many things you can do to play with teacups, it’s brilliant. The most obvious one is to get a teacup, get a spoon, tap the teacup around the rim and listen, and you will hear something strange. And the other thing is, push your toast off the table because you can, and you’ll learn stuff from it. And if you’re feeling really ambitious, try and push it off in such a way that it doesn’t fall butter-side down, which is possible.

The point of all of this is that, first of all, we should all play with toys. We shouldn’t be afraid to investigate the physical world for ourselves with the tools around us, because we all have access to them. It matters, because if we want to understand society, if we want to be good citizens, we need to understand the framework on which everything else must be based.

Playing with toys is great. Understanding how to keep our life-support systems going is great. But fundamentally, the thing that we need to change in the way that we talk about physics, is we need to understand that physics isn’t out there with weird people and strange hieroglyphics for somebody else in a posh lab. Physics is right here; it’s for us, and we can all play with it.

Thank you very much.

- Helen Czerski

- Science is not a collection of facts, it’s a method of asking questions, of testing ideas, of trying to understand the world around us.

- To understand the world, you have to see it from different perspectives. That’s what science is all about: looking at the same thing in many different ways to get a fuller picture.

- Science is too important to be left only to scientists. Everyone needs to understand how science works and why it matters to all of us.

- Curiosity is the engine of science, and the world is full of questions just waiting to be explored.