free photos website

command

1 | open -a "Google Chrome" index.html |

She escaped from the wreckage unscathed.

I detest pepperoni, and wouldn’t eat it if you paid me!

He enjoys playing pranks on his friends.

Do not prank me!

a room with good ventilation

scrounge a dollar from a friend

seeds sprouting in the spring

The garden is sprouting weeds.

I got a splinter in my finger.

There were splinters of glass everywhere.

He sprinkled water on the plants.

Rain splattered against the windows.

The kids sprawled on the floor to watch TV.

sprawled on the couch watching TV

The bushes were sprawling along the road.

The lottery jackpot is up to one million dollars.

the movie is expected to be the biggest blockbuster of the summer

The crisis is merely a phantom made up by the media.

She ripped the fabric in half.

He ripped open the package.

protesters were chanting outside

The students griped that they had too much homework.

Like a little child, he often moped when he didn’t get what he wanted.

The package was wrapped in brown paper and tied with twine.

The priest wore a purple robe.

She raged about the injustice of their decision.

Hey, dude, what’s up?

OK, dude, whatever you say.

a benevolent donor

a benevolent society

a benevolent organization

benevolent smiles

The lion’s mane

Green slime covers the surface of the pond.

vied with his colleagues for the coveted promotion

The recipe says that you should marinate the chicken overnight.

We were taught to chew our food thoroughly before swallowing.

You’re not allowed to chew gum in class.

dip fruit in melted chocolate to have a chocolate fondue

A borough is an administrative division in various English-speaking countries. In principle, the term borough designates a self-governing walled town, although in practice, official use of the term varies widely.

She was frowning when she entered the room, so I knew that she was annoyed about something.

The teacher gave me a scowl when I walked in late.

Beethoven’s iconic scowl

the dog growled at the stranger

a pot of boiling water

a pouting child

The boy didn’t want to leave—he stomped his feet and pouted.

several coyotes began howling close by as the sun went down

The difference between the slouch and standing straight up, was the difference between a negative and positive perception.

The boy was slouching over his school books.

a tiger prowling in the jungle

The police were prowling the streets in their patrol cars.

I prowled the store looking for sales.

a rowdy game of basketball

Listen, my children, and you shall hear

Of the midnight ride of Paul Revere,

On the eighteenth of April, in Seventy-five;

Hardly a man is now alive

Who remembers that famous day and year.

He said to his friend, “If the British march

By land or sea from the town to-night,

Hang a lantern aloft in the belfry arch

Of the North Church tower as a signal light,—

One, if by land, and two, if by sea;

And I on the opposite shore will be,

Ready to ride and spread the alarm

Through every Middlesex village and farm,

For the country folk to be up and to arm.”

Then he said, “Good night!” and with muffled oar

Silently rowed to the Charlestown shore,

Just as the moon rose over the bay,

Where swinging wide at her moorings lay

The Somerset, British man-of-war;

A phantom ship, with each mast and spar

Across the moon like a prison bar,

And a huge black hulk, that was magnified

By its own reflection in the tide.

Meanwhile, his friend, through alley and street,

Wanders and watches with eager ears,

Till in the silence around him he hears

The muster of men at the barrack door,

The sound of arms, and the tramp of feet,

And the measured tread of the grenadiers,

Marching down to their boats on the shore.

Then he climbed the tower of the Old North Church,

By the wooden stairs, with stealthy tread,

To the belfry-chamber overhead,

And startled the pigeons from their perch

On the sombre rafters, that round him made

Masses and moving shapes of shade, —

By the trembling ladder, steep and tall,

To the highest window in the wall,

Where he paused to listen and look down

A moment on the roofs of the town,

And the moonlight flowing over all.

Beneath, in the churchyard, lay the dead,

In their night-encampment on the hill,

Wrapped in silence so deep and still

That he could hear, like a sentinel’s tread,

The watchful night-wind, as it went

Creeping along from tent to tent,

And seeming to whisper, “All is well!”

A moment only he feels the spell

Of the place and the hour, and the secret dread

Of the lonely belfry and the dead;

For suddenly all his thoughts are bent

On a shadowy something far away,

Where the river widens to meet the bay, —

A line of black that bends and floats

On the rising tide, like a bridge of boats.

Meanwhile, impatient to mount and ride,

Booted and spurred, with a heavy stride

On the opposite shore walked Paul Revere.

Now he patted his horse’s side,

Now gazed at the landscape far and near,

Then, impetuous, stamped the earth,

And turned and tightened his saddle girth;

But mostly he watched with eager search

The belfry-tower of the Old North Church,

As it rose above the graves on the hill,

Lonely and spectral and sombre and still.

And lo! as he looks, on the belfry’s height

A glimmer, and then a gleam of light!

He springs to the saddle, the bridle he turns,

But lingers and gazes, till full on his sight

A second lamp in the belfry burns!

A hurry of hoofs in a village street,

A shape in the moonlight, a bulk in the dark,

And beneath, from the pebbles, in passing, a spark

Struck out by a steed flying fearless and fleet:

That was all! And yet, through the gloom and the light,

The fate of a nation was riding that night;

And the spark struck out by that steed, in his flight,

Kindled the land into flame with its heat.

He has left the village and mounted the steep,

And beneath him, tranquil and broad and deep,

Is the Mystic, meeting the ocean tides;

And under the alders, that skirt its edge,

Now soft on the sand, now loud on the ledge,

Is heard the tramp of his steed as he rides.

It was twelve by the village clock,

When he crossed the bridge into Medford town.

He heard the crowing of the cock,

And the barking of the farmer’s dog,

And felt the damp of the river fog,

That rises after the sun goes down.

It was one by the village clock,

When he galloped into Lexington.

He saw the gilded weathercock

Swim in the moonlight as he passed,

And the meeting-house windows, blank and bare,

Gaze at him with a spectral glare,

As if they already stood aghast

At the bloody work they would look upon.

It was two by the village clock,

When he came to the bridge in Concord town.

He heard the bleating of the flock,

And the twitter of birds among the trees,

And felt the breath of the morning breeze

Blowing over the meadows brown.

And one was safe and asleep in his bed

Who at the bridge would be first to fall,

Who that day would be lying dead,

Pierced by a British musket-ball.

You know the rest. In the books you have read,

How the British Regulars fired and fled, —

How the farmers gave them ball for ball,

From behind each fence and farm-yard wall,

Chasing the red-coats down the lane,

Then crossing the fields to emerge again

Under the trees at the turn of the road,

And only pausing to fire and load.

So through the night rode Paul Revere;

And so through the night went his cry of alarm

To every Middlesex village and farm, —

A cry of defiance and not of fear,

A voice in the darkness, a knock at the door,

And a word that shall echo forevermore!

For, borne on the night-wind of the Past,

Through all our history, to the last,

In the hour of darkness and peril and need,

The people will waken and listen to hear

The hurrying hoof-beats of that steed,

And the midnight message of Paul Revere.

Who would have imagined that something as straightforward as the natural numbers (1, 2, 3, 4,…) could give birth to anything so baffling as the prime numbers (2, 3 ,5, 7, 11, …)?

—— Ian Stewart

The ‘average’ distribution of primes is very regular; its density shows a steady but slow decrease. On the other hand the distribution of the primes in detail is extremely irregular. (G.H.Hardy)

God may not play dice with the universe, but something strange is going on with the prime numbers. (Carl Pomerance/Paul Erdős)

The prime number theorem shows that the primes have some large-scale structure, even though they can behave quite randomly at smaller scales.(Terence Tao)

On the other hand, the primes also have some local structure. For instance,(Terence Tao)

在整体上表现出正则性倾向而在局部却呈现出无规则性态,这是素数分布的一个值得注意的地方。

素数就像对物理学家极其重要的“理想气体”,客观地讲,其分布可以说是确定的,然而当我们试图描述它在一给定点的情况时,我们却观察到类似掷骰子碰运气的赌博那样的统计振荡。

素数如同理想气体那样占据着所能允许的整个空间(而这正意味着随机性),也就是说,素数在那些非常严格使之极端正则的限制性条件下有着充分的自由度。

在大多数关于素数的猜想中都隐含着这样的观点:任何不是显然不可能的实际都是可实现的。(Les Nombres Premiers)

我们可以用相当好的准确度来预测N以内素数的个数.另一方面,素数在一些短区间内的分布是相当没有规律的。这种既“随机”又可预测相组合便使得素数的分布既是有序的排列,同时又有意外的现象。Schroeder在他精彩的书《科学和通信中的数论》(1984)一书中,把这种现象称作是艺术作品的基本要素。许多数学家都认为素数分布问题具有极大的美学动力。(The little book of bigger primes)

The series \(\sum \frac{1}{p} = \frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{3} + \frac{1}{5} \dots \) is divergent. 而\( \sum_{n=1}^{\infty}\frac{1}{n^2} = \frac{\pi^2}{6} \),这说明质数是正整数集的真正有份量的子集

\(\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\prod _{p,\in ,\mathbb {P} }\left({\frac {1}{1-{\frac {1}{p^{s}}}}}\right) = \sum _{n=1}^{\infty }{\frac {1}{n^{s}}}.\end{aligned}}\)

holds for all s such that the left-hand side converges absolutely.

\( \sum _{n≤x} {\frac{1}{n}} = \log x + \gamma + O(1/x) \)

where \( \gamma \) is Euler-Mascheroni constant.

\( \gamma=0.577215664901532860651…. \)

\( \sum _{p≤x} {\frac{1}{p}} = \log \log x + B_1 + O(\frac{1}{\log x}) \)

where \( B_1 \) is Mertens constant.

\( B_1=0.2614972128… \).

The number obtained by adding the reciprocals of the odd twin primes, \( B≡(1/3+1/5)+(1/5+1/7)+(1/11+1/13)+(1/17+1/19)+… \), By Brun’s theorem, the series converges to a definite number, which expresses the scarcity of twin primes, even if there are infinitely many of them.

B≈1.902160583104

\(log x \) tends to infinity more slowly than any positive power of x.

\(\frac{log x}{x^δ} → 0 \) for every positive δ.

The function \( \frac{x}{log x} \) tends to infinity more slowly than x but more rapidly than \( x^{1-δ} \), and it is the simplest function which has this property.

The number of primes not exceeding x is asymptotic to \( \frac{x}{log x} \).

The nth prime is approximately equal to \( nln n \).

\( \displaystyle \pi (x)\sim {\frac {x}{\log x}} \).

\( \displaystyle \pi (x)\sim \operatorname {Li} (x)=\int _{2}^{x}{\frac {dt}{\log t}}=\operatorname {li} (x)-\operatorname {li} (2). \)

\( \displaystyle \pi (x)=\operatorname {Li} (x)+O\left({\sqrt {x}}\log x\right) \)

\( \forall \varepsilon > 0, \pi (x)=\operatorname {Li} (x)+O(x^{\frac{1}{2}+ε}) \)

\( \displaystyle \pi (x) \) greater than the ‘logarithm integral’ \( \operatorname {Li} (x) \) depends upon the largeness of \( log log log x \) for large x.

John Edensor Littlewood found that the sign of the difference \( \pi (x)-\operatorname {Li} (x) \) changes infinitely often.

Any prime number,except 2 or 3,is 6n+1 or 6n+5.

素数表显示了素数的混沌特性,而其表面的无序性最终却与一些,比如说源于物理现象的经典随机模型相吻合。

完全随机即混沌具有无穷大的复杂度;另一方面,整数的复杂度显然是随其大小的增加而增大;在无穷远处,整数序列表现出随机的性状,因而素数序列也蕴涵着随机性。(Les Nombres Premiers)

Probabilistic number theory: different prime numbers are, in some serious sense, like independent random variables.

Dynamical: the prime numbers were seen to be moving particles in a 1-dimensional continuum

Cramér & 模1一致分布: 素数序列看起来就像一个受同样增长性约束的随机序列

素数似乎达到了他们所能被允许的随机性的极限。

素数的整体分布参数不足以用来描述它们局部的不规则性。

Mathematicians have tried in vain to this day to discover some order in the sequence of prime numbers, and we have reason to believe that it is a mystery into which the mind will never penetrate. - Leonard Euler

The problem of distinguishing prime numbers from composite numbers and of resolving the latter into their prime factors is known to be one of the most important and useful in arithmetic. It has engaged the industry and wisdom of ancient and modern geometers to such an extent that it would be superfluous to discuss the problem at length…Further, the dignity of the science itself seems to require that every possible means be explored for the solution of a problem so elegant and so celebrated. - G.F.Gauss

The sequence of primes behaves “unpredictably” or “randomly”, we do not have a (useful) exact formula for the nth prime number pn!

Despite not having a good exact formula for the sequence of primes, we do have a fairly good inexact formula as Prime number theorem.

The von Mangoldt function(as an analogy, sound wave) which is noisy at prime number times, and quiet at other times.

Fourier transforms is just like listenning to this wave and record the notes that you hear (the zeroes of the Riemann zeta function, or the “music of the primes”). Each such note corresponds to a hidden pattern in the distribution of the primes.

The infamous Riemann hypothesis predicts a more precise formula for pn, which should be accurate to an error of about \( \sqrt n \).

If the Riemann hypothesis is true, we can remove one exponential.

Interestingly, the error \( O(\sqrt n ㏑^3 n) \) predicted by the Riemann hypothesis is essentially the same type of error one would have expected if the primes were distributed randomly. (The law of large numbers)

Thus the Riemann hypothesis asserts (in some sense) that the primes are pseudorandom - they behave randomly, even though they are actually deterministic.

The type of pseudorandomness properties which underlie cryptographic protocols are not the same as the type of pseudorandomness properties which underlie conjectures such as the Riemann hypothesis; thus for instance a solution to the Riemann hypothesis would be a dramatic event in pure mathematics, but would not directly impact cryptographic security.

Sieves study the set of primes in aggregate, rather than trying to focus on each prime individually.

The sieve now captures not only primes, but also almost primes - numbers with very few prime factors.

We are still unable to detect several types of patterns in the primes. However, we have made recent progress on one type of pattern, namely an arithmetic progression.

I actually haven’t thought seriously about RH since some very naive attempts at it in graduate school. It’s possible that one could approach this problem by finding out more structure in the zeta function, but my (somewhat uninformed) opinion is that zeta is inherently a rather pseudorandom object (except of course for its obvious structural properties such as meromorphicity, asymptotics, and the functional equation), and it may be better to return to the prime number side of things, for instance by locating a new proof of the prime number theorem, or finding a way to exclude Siegel zeroes and obtain a more effective prime number theorem in arithmetic progressions. But it’s hard to see how current methods can hope to get the type of power gain in the error terms for prime statistics which would be needed for the full RH; some radically new idea would be needed for that, probably. - see http://terrytao.wordpress.com/2008/01/07/ams-lecture-structure-and-randomness-in-the-prime-numbers, AMS lecture: Structure and randomness in the prime numbers

The music of the primes is a chord?

Atle Selberg: If anything at all in our universe is correct, it has to be the Riemann hypothesis, if for no other reasons, so for purely esthetical reasons. The simple ideas are the ones that will survive.

J. Brian Conrey: RH tells us that the primes are distributed in as nice a way as possible. If RH were false, there would be some strange irregularities in the distribution of primes; the first zero off the line would be a very important mathematical constant. It seems unlikely that nature is that perverse!

Enrico Bombieri: The failure of the Riemann hypothesis would create havoc in the distribution of prime numbers.

Marcus du Sautoy: As we shall see, Riemann’s Hypothesis can be interpreted as an example of a general philosophy among mathematicians that, given a choice between an ugly world and an aesthetic one, Nature always chooses the latter.

The symptoms of the disease include fever, nausea, and diarrhea.

Norovirus, the culprit behind a nasty stomach bug, is rising again in Canada

clean up after someone with Norovirus vomits or has Diarrhea

Vomit and poop can splatter in all directions

clean up must be very thorough to not miss any drops of vomit or poop you can’t see.

person creates a prompt

generative AI generates a noval artifact

strong work ethics

traffic congested the highways

congested streets

convex lenses are used to correct for farsightedness

flip a coin

flip a pancake

a bland smile

bland diet

chicken nuggets

a picky eater

at first blush

The fruit is yellow, with a blush of pink.

She braids her hair every morning.

until she was 15, she had a braid that reached to her knees

a writer of advertising or publicity copy

aromatic herbs

aromatic flowers can add greatly to the ambience of a room

the deafening roar of the planes

The deafening thunder frightened all the children.

Coleslaw is the correct spelling for the cabbage-based side salad often served alongside barbecue.

Reporter: Why did you want to climb Mount Everest?

George Mallory: Because it’s there

Those famous words were spoken by British climber George Mallory in 1923, by the time he was interviewed for the New York Times.

Mallory’s body was eventually found in 1999, on the north face of the mountain.

George Pólya: If you want to climb the Matterhorn, you might first wish to go to Zermat, where those who have tried are buried.

I will make it

Keep going west

Fifty years ago a physician sailed across the Atlantic, unassisted, in a kayak to test the stresses on the human body and see if it was possible to survive for long periods at sea. It was a voyage that nearly killed him. His voyage made world headlines and showed him it was possible to survive for long periods at sea. Lindemann was by no means the first person to cross the Atlantic alone, but his feat was one of the most daring crossings in history.

In 1957 Lindemann published a best-selling book Alone at Sea

This is my first memory:

A big room with heavy wooden tables that sat on a creaky

wood floor

A line of green shades—bankers’ lights—down the center

Heavy oak chairs that were too low or maybe I was simply

too short

For me to sit in and read

So my first book was always big

In the foyer up four steps a semi-circle desk presided

To the left side the card catalogue

On the right newspapers draped over what looked like

a quilt rack

Magazines face out from the wall

The welcoming smile of my librarian

The anticipation in my heart

All those books—another world—just waiting

At my fingertips.

We have a dinner engagement this weekend.

Consult more than one financial adviser before making a final choice, and trust your gut.— Quentin Fottrell

My gut says this is, overall, a terrible idea.— Erica Buist

a gut feeling

Your gut can help you determine which decision suits you best.

a gut reaction

His fear of crowds eventually developed into a phobia.

Social phobia (SOP) and selective mutism (SM) are related anxiety disorders characterized by distress and dysfunction in social situations. SOP typically onsets in adolescence and affects about 8% of the general population, whereas SM onsets before age 5 and is prevalent in up to 2% of youth.

You could see through the slit in the fence.

I slit the bag open at the top.

It seems better to reanimate the contents learned yesterday before acquiring new ones.

What Lights the Universe’s Standard Candles?

Type Ia supernovas are astronomers’ best tools for measuring cosmic distances.

The frigid gusts of wind stung their faces.

The temperature there is a frigid -400 degrees Fahrenheit—colder than the surface of Pluto, and just a tad warmer than absolute zero. — Katrina Miller, WIRED, 13 Dec. 2022

He was vilified in the press for his comments.

Terrain affects surface water flow and distribution. Over a large area, it can affect weather and climate patterns.

We hiked through a variety of terrains.

They will pressure you, and you must try not to succumb.

Older people are more likely to succumb to the ravages of COVID-19. — Mary Kekatos, ABC News, 19 Nov. 2022

ingrain young children with responsibility

It is in our homes and classrooms that lifelong attitudes are ingrained.

The Sun (2007)

Each day we make countless choices and live out deeply ingrained habits that all add up to a lifestyle.

Christianity Today (2000)

ingrain carpet

The animals got ensnared in the net.

The police successfully ensnared the burglar.

The accident was the result of a series of blunders.

fixed a minor blunder in the advertising flyer

He busted his watch when he fell.

Two students got busted by the teacher for smoking in the bathroom.

boom and bust

She has a knack for telling interesting stories.

has a knack for making friends

I can attest that what he has said is true.

the result attests the truth of that statement

Her office is at the end of the hallway.

A hallway or corridor is an interior space in a building that is used to connect other rooms. Hallways are generally long and narrow.

Bill Gates gets ‘called out’ for being a ‘climate hypocrite’

Bill Gates has confronted accusations that he is a “hypocrite” as he uses his private jet while he is campaigning for technologies designed to support global efforts to tackle climate change.

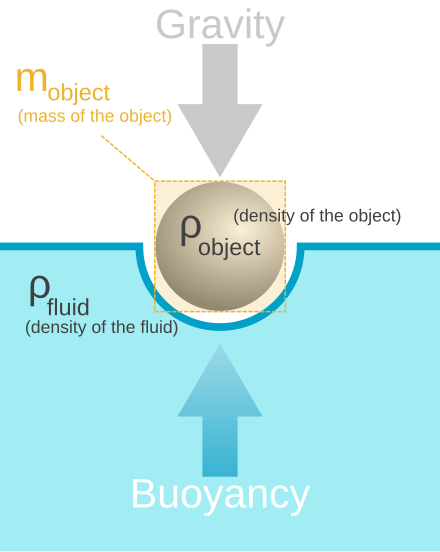

the buoyancy of a cork in water

the buoyancy of seawater

The swimmer is supported by the water’s buoyancy.

He quickly developed a good rapport with the other teachers.

There is a lack of rapport between the members of the group.

One must have a mind of winter

To regard the frost and the boughs

Of the pine-trees crusted with snow;

And have been cold a long time

To behold the junipers shagged with ice,

The spruces rough in the distant glitter

Of the January sun; and not to think

Of any misery in the sound of the wind,

In the sound of a few leaves,

Which is the sound of the land

Full of the same wind

That is blowing in the same bare place

For the listener, who listens in the snow,

And, nothing himself, beholds

Nothing that is not there and the nothing that is.

Today is very boring,

It’s a very boring day,

There is nothing much to look at,

There is nothing much to say,

There’s a peacock on my sneakers,

There’s a penguin on my head,

There’s a dormouse on my doorstep,

I am going back to bed.

Today is very boring,

It is boring through and through,

There is absolutely nothing

That I think I want to do,

I see giants riding rhinos,

And an ogre with a sword,

There’s a dragon blowing smoke rings,

I am positively bored.

Today is very boring,

I can hardly help but yawn,

There’s a flying saucer landing

In the middle of my lawn,

A volcano just erupted

Less than half a mile away,

And I think I felt an earthquake,

It’s a very boring day.